The

Flower Ornament Scripture

A

Translation of the Avatamsaka Sutra

Thomas

Cleary

Introduction

THE FLOWER ORNAMENT SCRIPTURE, called Avatamsaka in Sanskrit and

Huayan in Chinese, is one of the major texts of Buddhism. Also referred to as

the major Scripture of Inconceivable Liberation, it is perhaps the richest and

most grandiose of all Buddhist scriptures, held in high esteem by all schools

of Buddhism that are concerned with universal liberation. Its incredible wealth

of sensual imagery staggers the imagination and exercises an almost mesmeric

effect on the mind as it conveys a wide range of teachings through its complex

structure, its colorful symbolism, and its mnemonic concentration formulae.

It is not known when or by whom this scripture was composed. It is

thought to have issued from different hands in the Indian cultural sphere

during the first and second centuries AD, but it is written so as to embrace a

broad spectrum of materials and resists rigid systematization. While standard

figures and images from Indian mythology are certainly in evidence here, as in

other Buddhist scriptures, it might be more appropriate to speak of its

provenance in terms of Buddhist culture rather than Indian culture per se. The

Flower Ornament Scripture presents a compendium of Buddhist teachings; it

could variously be said with a measure of truth in each case that these

teachings are set forth in a system, in a plurality of systems, and without a

system. The integrity of Buddhism as a whole, the specificity of application of

its particular elements, and the interpenetration of those elements are

fundamental points of orientation of the unfolding of the scripture.

Historicity as such is certainly of little account in The Flower

Ornament Scripture. This is generally true of the Mahayana Buddhist scriptures,

although they usually present their teachings as having been revealed or

occasioned by the meditations of the historical Buddha Shakyamuni. In the case of

The Flower Ornament Scripture, most of the discourse is done by

transhistorical, symbolic beings who represent aspects of universal

enlightenment. The Buddha shifts from an individual to a cosmic principle and

manifestations of that cosmic principle; the "Buddha" in one line

might be "the Buddhas" in the next, representing enlightenment itself,

the scope of enlightenment, or those who have realized enlightenment.

Certainly one of the most colorful and dramatic rehearsals of

Buddhist teachings, The Flower Ornament Scripture became one of the pillars of

East Asian Buddhism. It was a source of some of the very first Buddhist

literature to be introduced to China, where there eventually developed a major

school of philosophy based on its teachings. This school spread to other parts

of Asia, interacted with other major Buddhist schools, and continues to the

present. The appreciation of The Flower Ornament Scripture was not, however, by

any means confined to the special Flower Ornament school, and its influence is

particularly noticeable in the literature of the powerful Chan (Zen) schools.

The work of translating from The Flower Ornament Scripture into Chinese apparently began in the second century AD, and continued for the better part of a thousand years. During this time more than thirty translations and retranslations of various books and selections from the scripture were produced. Numerous related scriptures were also translated. Many of these texts still exist in Chinese. Comprehensive renditions of the scripture were finally made in the early fifth and late seventh centuries. The original texts for both of these monumental translations were brought to China from Khotan in Central Asia, which was located on the Silk Route and was a major center for the early spread of Buddhism into China. Khotan, where an Indo-Iranian language was spoken, is now a part of the Xinjiang (Sinkiang) Uighur autonomous region in China, near Kashmir, another traditional center of Buddhist activity. The first comprehensive translation of The Flower Ornament Scripture was done under the direction of an Indian monk named Buddhabhadra (359-429); the second, under the direction of a Khotanese monk named Shikshananda (652-710) . The latter version, from which the present English translation is made, was based on a more complete text imported from Khotan at the request of the empress of China; it is somewhat more than ten percent longer than Buddhabhadra's translation.

The Flower Ornament Scripture, in Shikshananda's version, contains

thirty-nine books. By way of introduction to this long and complex text, we

will focus on a comparison of The Flower Ornament Scriptu re with other major

scriptures; as well as a brief glance at the main thrust of each book.

A Comparison with Other Major Buddhist Scriptures

Due to the great variety in Buddhist scriptures, analysis of their

interre lation was an integral part of Buddhist studies in East Asia, where

scriptures were introduced in great quantities irrespective of their time or

place of origin. In order to convey some idea of the Buddhism of The Flower

Ornament Scripture in respect to other major scriptures, as well as to

summarize some of the principal features of The Flower Ornament , we will begin

this Introduction with a comparison of The Flower Ornament with other important

scriptures. This discussion will be based on the "Discourse on the Flower

Ornament," a famous commentary by an eighth century Chinese lay Buddhist,

Li Tongxuan. What follows is a free rendering of Li's comparisons of The Flower

Ornament Scripture to the scriptures of the lesser vehicle (the Pali Canon), 1

the Brahmajala Scripture, the Prajnaparamita Scriptures, 2 the Sandhinirmocana

Scriptu re, the Lankavatara Scripture, 3 the Vimalakirtinirdesa Scripture, 4

the Saddharmapun darika Scripture, 5 and the Mahaparinirvana Scripture. 6

The scriptures containing the precepts of the lesser vehicle are

based on conceptual existence. The Buddha first told people what to do and what

not to do. In these teachings, relinquishment is considered good and

nonrelinquishment is considered not good.

Doctrine set up this way is not yet to be considered indicative of true

existence. This teaching based on existence is temporary, dealing with the

delusions of ordinary feelings and the arbitrary invention of ills; this

teaching is designed to stop these and enable people to live in truly human or

celestial states. That is why the preface of the precepts says that if one

wants to live in heavenly or human conditions one should always keep the

precepts.

People's fabricated doings are unreal, and not true attainment,

therefore their life in human and celestial states is impermanent, not truly

real. They have not yet attained the body of reality and the body of knowledge.

This teaching is not based on true existence; it is temporarily based on conceptual

existence. This is the model of the lesser vehicle. As for keeping precepts in

The Flower Ornament Scripture, it is not this way: as it says in the scripture,

"Is the body religious practice? Are walking, standing, sitting, or

reclining religious practice?" and so on, examining closely in search of

"religious practice, " ultimately finding it cannot be

apprehended-this ungraspability is why it is called pure religious prac tice.

As the scripture says, those engaged in such pure practice are said to uphold

the discipline of the buddha-nature, and attain the Buddha's reality body.

Therefore they attain enlightenment at the first inspiration. Because they keep

the discipline of buddha-nature, they are equal to the essence of Buddha, equal

in terms of noumenon and phenomenon, merging with the cosmos of reality. When

they keep discipline this way, they do not see themselves keeping precepts,

they do not see others breaking precepts. Their action is neither that of

ordinary people nor that of saints. They do not see themselves arousing the

determination for enlightenment, they do not see the Buddhas attaining

enlightenment. If there is anything at all that can be grasped or

apprehended-whether good or bad-this is not called enlightenment, not called

pure practice. One should see in this way. Such discipline based on the essence

is itself the body of reality; the body ofreality is the knowledge of Buddhas;

the knowledge of Buddhas is true enlightenment. Therefore this discipline of The Flower

Ornament Scripture is not the same as the teaching of the lesser vehicle, which

has choosing and rejection.

Next, the precepts for enlightening beings in the Brahmajala

Scripture are based on presentation of both conceptual existence and real

existence. For people who have big hearts and like to practice kindness and

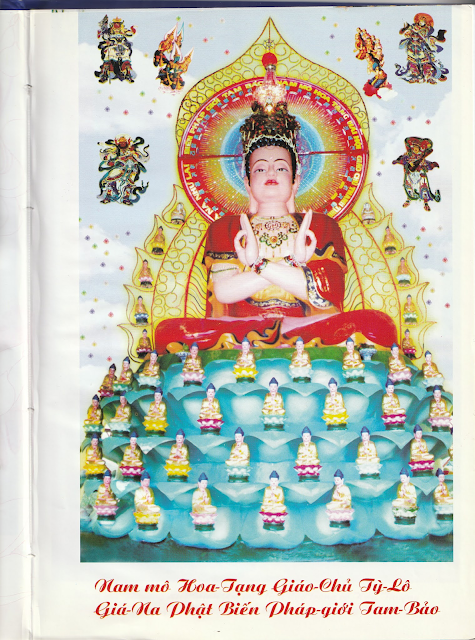

compassion and those who seek Buddhahood, the Buddha says Vairocana is the

fundamental body, with ten billion emanation bodies. To suddenly cause us to

recognize the branches and return to the root, the scripture says these ten

billion bodies bring innumerable beings to the Buddha. It also says if people

accept the precepts of Buddha, they then enter the ranks of Buddhas: their rank

is already the same as great enlightenment and they are true offspring of Buddha.

This is therefore discipline based on the essence, and is thus based on

reality. This scripture abruptly shows great-hearted people the discipline of

the essence of the body of reality, while lesser people get it gradually.

Therefore one teaching responds to two kinds of faculties, greater and lesser.

The statement that the ten billion emanation bodies each bring countless beings

to the Buddha illustrates giving up the provisional for the true. This is the

teaching of true existence. Because in this teaching the provisional and true

arc shown at once, it is not the same as the lesser vehicle, which begins with

impermanence and has results that are also impermanent, because the precepts of

the lesser vehicle only lead to humanity and heavenly life. However, the

establishment of a school of true existence in the Brahmajala Scripture is not

the same as that expounded by Vairocana in The Flower Ornament Scripture. In

the Brahmajala Scriptu re, by following the teaching of the emanation bodies of

Buddha we arrive at the original body: in the school of the complete teaching

of the Flower Ornament, the original body is shown all at once; the fundamental

realm of reality, the body of rewards of great knowledge, cause and effect, and

noumenon and phenomena are equally revealed. Also the description of the extent

of the cosmos of The Flower Ornament Scripture is not the same as the

description in the Brahmajala Scripture.

As for the Prajnaparamita

Scriptures, they are based on

explaining emptiness in order to show the truth. When the Buddha first

expounded the teachings of the lesser vehicle to people, they stuck to

principles and phenomena as both real, and therefore could not get rid of

obstruction. Therefore Buddha explained emptiness to them, to break down their

attachments. That is why it explains eighteen kinds of emptiness in the

Prajnaparamita Scriptures-the world, the three treasures (the Buddha, the

Teaching, and the Community), the four truths (suffering, origin, ex tinction,

the path), the three times (past, present, and future) , and so on, are all

empty, and emptiness itself is empty too. This is extensively explained in

these scriptures, to nullify ignorance and obstructing ac tions. When

ignorance is totally exhausted, obstructing actions have no essence-nirvana

naturally appears. This is true existence; it is not called a school of

emptiness. However, though it is real true existence, many of the teachings

expounded have becoming and disintegration, therefore it cannot yet be

considered complete. As for The Flower Ornament Scripture, in it are the arrays

of characteristics and embellishments that are rewards or consequences of

enlightening practice-they can be empty and they can be actual. In this

scripture the teachings of emptiness and existence arc not applied

singly-noumenon and phenomena, emptiness and exis tence, interpenetrate,

reflecting each other. All the books of the whole Flower Ornament Scripture

interpenetrate, all the statements

intertwine. All the sayings in the scripture point to the same thing-when

one becomes all become, when one disintegrates all disintegrate. In the totality, because the essence is equal,

the time is equal, and the practice is equal, every part of the scripture is

equal, and so the explanations of the Teaching are equal. Therefore attainment

of buddhahood in the present means

equality with all Buddhas of past, present, and future: consequently there is

no past, present, or future-no time.

In this it differs from the Prajnaparamita

Scriptures, in which formation and disin tegration take place at separate

times and thus cause and effect are successive.

Now as for the Sandhinirmocana Scripture, this is based on

nonvoidness and nonexistence. Buddha explained this teaching after having ex pounded teachings of existence and of

emptiness, to harmonize the two views of being and nothingness, making it

neither emptiness nor exis tence. To this end he spoke of an unalloyed pure

consciousness without any defilement. According to this teaching, just as a rapid

flow of water produces many waves , all of which arc equally based on the

water, similarly the sense consciousnesses, the conceptual consciousness, the

judgmental consciousness, and the cumulative repository consciousness are all

based on the pure consciousness. As the Sandhinirmocana Scripture says, it is

like the face of a good mirror: if one thing which casts a reflection comes

before it, just one image appears; if two or more things come before it, two or

more images appear-it is not that the

surface of the mirror changes into reflections, and there is no manipulation or

annihilation that can be grasped either. This illustrates the pure con

sciousness on which all aspects of consciousness are based.

The Sandhinirmocana Scripture also says that though the

enlightening being lives by the teaching, knowledge is the basis, because the teaching is a construction. The

intent of this scripture is to foster clear understanding of the essence of

consciousness in the medium of consciousness. Because fundamentally it is only

real knowledge, it is like the stream of water, which produces waves without

leaving the body of the water. It is also like a clear mirror, which due to its

pure body contains many images without discrimination, never actually having anything

in it, yet not impeding the existence of images. Likewise, the forms of

conscious ness manifested by one's own mind are not apart from essential uncontrived

pure knowledge, in which there arc no attachments such as self or other, inside

or outside, in regard to the images manifested . Letting consciousness function

freely, going along with knowledge, this breaks up bondage to emptiness or

existence, considering everything neither empty nor existent. Therefore a verse

of the Sandhinirmocana Scripture says, "The pure consciousness is very

deep and subtle; all impressions are like a torrent. I do not tell the ignorant

about this, for fear they will cling to the notion as 'self.' " The

statement that the pure consciousness is very deep and subtle is to draw

ordinary people into realization of knowledge in consciousness: it is not the

same as the breaking down of forms into emptiness, which is practiced by the

two lesser vehicles and the beginning enlightening beings learning the gradual

method of en lightenment. It is also not the same as ordinary people who cling

to things as really existent. Because it is not the same as them, it is not

emptiness, not existence. What is not empty? It means that knowledge can, in

all circumstances, illumine the situation and help people. What is not

existent? It means that when knowledge accords with circumstances, there is no

distinction of essence and characteristics, and thus there is no birth,

subsistence, or extinction. Based on these meanings it is called "not empty,

not existent. "

While the Sandhinirmocatza Scripture in this way lets us know, in

terms of consciousness, that emptiness and existence are nondual, The Flower

Ornament Scripture is not like this: The Flower Ornament just reveals the

Buddha's essence and function of fundamental knowledge of the one reality, the

fundamental body, the fundamental cosmos.

Therefore it merges true essence and characteristics, the oceans of the

reality body and the body of consequences of deeds, the reward body. It directly points out at once to people of

the highest faculties the basic knowledge of the unique cosmos of reality, the

qualities of Buddhahood. This is its way of teaching and enlightenment; it does

not discuss such phenomena as producing consciousness according to illusion.

According to the Saddharmapundarika Scripture, Buddha appears in

the world to enlighten people with Buddha-knowledge and purify them, not for

any other religious vehicle, no second or third vehicle. Also it says that

Buddha does not acknowledge the understanding of the essence and

characteristics of Buddha by people of the three vehicles . Therefore the

Saddharmapundarika Scripture says, "As for the various meanings of essence

and characteristics, only I and the other Buddhas of the ten directions know

them-my disciples, individual illuminates, and even nonregressing enlightening

beings cannot know them. " Because the Saddharmapundarika Scripture joins

the temporary studies of the three vehicles and brings them ultimately to the

true realm of reality of the Buddha-vehicle, its doctrine to some extent

matches that of The Flower Ornament Scripture.

The Flower Ornament Scripture directly reveals the door of

consummate buddhahood, the realm of reality, the fundamental essence and

function of the cosmos, communicating this to people of superior faculties so

that they may awaken to it: it does not set up the provisional didactic device

of five, six, seven, eight, and nine consciousnesses like the Sandhinirmo cana

Scripture does. As for the Sandhinirmocana Scripture's establishment of a

ninth, pure consciousness, there are two meanings. For one thing, it is for the

sake of those of the two lesser vehicles who have long sickened of birth and

death and cultivate emptiness to annihilate consciousness, aiming directly for

empty quiescence. Also, in the next phase, the Prajnaparamita Scrip tures talk

a lot about emptiness and refute the notion of existence, to turn around the

minds of the two vehicles as well as enlightening beings engaged in gradual

study. They also make the six ways of transcendence the vehicle of practice.

Although some of those in the two vehicles are converted, they and the

gradual-practice enlighten ing beings are predominantly inclined toward

emptiness. This is because the elementary curative teachings for the

gradual-study enlightening beings are similar to some extent to those for the

lesser vehicles; they do have, however, a bit more compassion than the latter.

They have not yet realized principles such as that of the body of reality, the

buddha-nature, and fundamental knowledge. They only take the avenue of

emptiness as their vehicle of salvation and the six ways of transcendence as

their form of practice. Their elementary curative means are after all the same

as the two vehicles-only by

contemplation of impermanence, impurity, bleached bones, atoms, and so on,

do they enter contemplation of emptiness. But while the two vehicles head for

extinction, enlightening beings stay in life. They subdue notions of self and

phenomena by means of contemplations of voidness, selflessness, and so on.

Basically this is not yet fundamental knowledge of the body of reality and the

buddha nature; because their vision is not yet true, inclination toward

emptiness is dominant. For this reason the Sandhinirmocana Scripture

expediently sets up a pure consciousness distinct from the conceptual,

judgemental, and cumulative consciousnesses, saying that these consciousnesses

rest on the pure consciousness.

The Sandhinirmocana Scripture does not yet directly explain that

the impressions in the cumulative or repository consciousness are the matrix of

enlightenment. This is because the students are engaged in learning out of fear

of suffering; if they were told that the seeds of action are eternally real, they

would become afraid and wouldn't believe it, so the scripture temporarily sets

up a "pure consciousness" so that they won't annihilate the conscious

nature and will grow in enlightenment. For this reason the Vimalakirtinirdesa

Scripture says, "They have not yet fulfilled buddhahood, but they don't annihilate sensation to get

realization." Since sensation is not annihilated, neither are conception

and conscious ness. As for the Lankavatara Scripture, it does directly tell

those whose faculties are mature that the seeds of action in the cumulative

"store house" consciousness are the matrix of enlightenment. The

Vimalakirti nirdesa Scripture says, "The passions which accompany us are

the seeds of buddhahood. ''

People who practice the Way are different, on different paths,

with myriad different understandings and ways of acting. Beyond the two

vehicles that are called the lesser vehicles, the vehicle of enlightening

beings has four types that are not the same: one is that of enlightening beings

who cultivate emptiness and selflessness; second is that of enlightening beings

who gradually see the buddha-nature; third is that of enlightening beings who

see buddha-nature all of a sudden; fourth is those enlightening beings who, by

means of the inherently pure knowl edge of the enlightened, and by means of

various levels of intensive practice, develop differentiating knowledge, fulfill

the practice of Universal Good and develop great benevolence and compassion.

As for the Lankavatara Scripture, its teaching is based on five

elements, three natures, eight consciousnesses, and twofold selflessness. The

five elements are forms, names, arbitrary conceptions, correct knowledge, and thusness. The three

natures are the nature of mere imagination, the nature of relative existence,

and the nature of absolute emptiness: the imaginary nature means the

characteristics of things as we conceive of them are mere descriptions,

projections of the imagination; the relative nature means that things exist in

terms of the relation of sense faculties, sense data, and sense consciousness;

the absolute nature means that the imaginary and relative natures are not in

themselves ultimately real. The eight consciousnesses are the five

sense-consciousness, the conceptual consciousness, the discriminating

judgemental consciousness, and the cumulative or repository

"storehouse" consciousness. The twofold self lessness is the

selflessness of persons and of things.

According to this scripture, there is a mountain in the south seas

called Lanka, where the Buddha expounded this teaching. This mountain is high

and steep and looks out over the ocean; there is no way of access to it, so

only those with spiritual powers can go up there. This represents the teaching

of the mind-ground, to which only those beyond cultivation and realization can

ascend. "Looking out over the ocean" represents the ocean of mind

being inherently clear, while waves of consciousness are drummed up by the wind

of objects. The scripture wants to make it clear that if you realize objects

arc inherently empty the mind-ocean will be naturally peaceful; when mind and

objects are both stilled, everything is revealed, just as when there is no wind

the sun and moon are clearly reflected in the ocean.

The Lankavatara Scripture is intended for enlightening beings of

mature faculties, all at once telling them the active consciousness bearing

seed like impressions is the matrix of enlightenment. Because these enlight

ening beings arc different from the practitioners of the two lesser vehicles

who annihilate consciousness and seek quiescence, and because they are

different from the enlightening beings of the Prajnaparamita Scriptures who

cultivate emptiness and in whom the inclination toward emptiness is dominant,

this scripture directly

explains the total reality of the fundamental

nature of the substance of consciousness, which then be comes the function of

knowledge. So just as when there is no wind on the ocean the images of objects

become clearer, likewise in this teaching of the mind ocean if you comprehend

that reality is consciousness it becomes knowledge. This scripture is different

from the idea of the Sandhinirmocana Scripture, which specially sets up a ninth

"pure" consciousness to guide beginners and gradually induce them to

remain in the realm of illusion to increase enlightenment, not letting their

minds plant seeds in voidness, and not letting their minds become like spoiled

fruitless seeds by onesidedly rejecting the world. So the Sandhinirmocana

Scripture is an elementary gateway to entry into illusion, while the

Lankavatara and Vimalakirtinirdesa Scriptures directly point to the funda

mental reality of illusion. The Lankavatara explains the storehouse con

sciousness as the matrix of enlightenment, while the Vimalakirtinirdesa

examines the true character of the body, seeing it to be the same as Buddha.

The Lankavatara and Vimalakirtinirdesa Scriptures are roughly

similar, while the Sandhinirmocana is a bit different. The Flower Ornament is

not like this: the body and sphere of the Buddha, the doors of teaching, and

the forms of practice are far different. It is an emanation body which expounds

the Lankavatara, and the realm explained is a defiled land; the location is a

mountain peak, and the teaching explains the realm of consciousness as real;

the interlocutor is an enlightening being called Great Intellect, the teaching

of the emanation Buddha is temporary, and the discourse of Great Intellect is

selective. As for the teaching of The Flower Ornament Scripture, the body of

Buddha is the fundamental reality, the realm of the teaching and its results is

the Flower Treasury; the teaching it rests on is the fruit of buddhahood, which

is entered through the realm of reality; the interlocutors are Manjushri and

Universally Good. The marvelous function ofknowledge ofnoumenon and phenom

ena, the aspects of practice of five sets of ten stages, and their causes and

effects , merge with each other; the substances of ten fields and ten bodies of

buddhahood interpenetrate. It would be impossible to tell fully of all the

generalities and specifics of The Flower Ornament.

Next, to deal with the Vimalakirtinirdesa Scripture, this is based

on inconceivability. The Vimalakirtinirdesa Scripture and The Flower Ornament

Scripture have ten kinds of difference and one kind of similarity. The spheres

of difference are: the arrays of the pure lands; the features of the body of

Buddha as rewards of religious practice

or emanated phantom manifestations; the inconceivable spiritual powers; the

avenues of teaching set up to deal with particular faculties ; the

congregations who come to hear the teachings; the doctrines set up; the

activity manifested by the enlightening being Vimalakirti; the location of the

teaching; the com pany of the Buddha; and the bequest of the teaching. The one

similarity is that the teachings of methods of entry into the Way are generally

alike.

First, regarding the difference in the arrays of the pure lands, in the case of the

pure land spoken of in the Vimalakirtinirdesa Scripture Buddha presses the

ground with his toe, whereupon the billion-world universe is adorned with

myriad jewels, like the land of Jewel Array Buddha, adorned with the jewels of

innumerable virtues. All in the assembly rejoice at this wonder and see

themselves sitting on jewel lotus blossoms. But this scripture still does not

speak of endless arrays of buddha-lands being in one atom. The Flower Ornament

Scripture fully tells of ten realms of Vairocana Buddha, ten Flower Treasury

oceans of worlds-each ocean of worlds containing endless oceans of worlds,

interpenetrating each other again and again, there being endless oceans of

worlds within a single atom. The complete sphere of the ten Buddha-bodies and

the sphere of sentient beings interpenetrate without mutual obstruction; the

arrays of myriad jewels are like lights and reflections. This is extensively

recounted in The Flower Ornament Scripture; it does not speak of the

purification and adornment of only one billion-world universe.

Second, regarding the difference in the features of the Buddhas'

bodies, being rewards or emanations, the Vimalakirti Scripture is ex pounded

by an emanation Buddha with the thirty-two marks of great ness, whereas The

Flower Ornament is expounded by the Buddha of true reward, with ninety-seven

marks of greatness and also as many marks as atoms in ten Flower Treasury

oceans of worlds.

Third, the difference in inconceivable spiritual powers: according

to the Vimalakirti Scrip ture's explanation of the spiritual powers of enlight

ening beings, they can fit a huge mountain into a mustard seed and put the

waters of four oceans into one pore; also Vimalakirti's little room is able to

admit thirty-two thousand lion thrones, each one eighty-four thousand leagues high.

Vimalakirti takes a group of eight thousand enlightening beings, five hundred

disciples, and a hundred thousand gods and humans in his hand and carries them

to a garden; also he takes the eastern buddha-land of Wonderful Joy in his hand

and brings it here to earth to show the congregation, then returns it to its

place. These miraculous powers are just shown for the benefit ofdisciples and

enlight ening beings who arc temporarily studying the three vehicles . Why?

Because disciples and enlightening beings studying the temporary teach ings do

not yet see the Way truly, and have not yet forgotten the distinction of self

and other. The miracles shown are based on the perception of the sense

faculties , and all have coming and going, bound aries and limits. Also they

are a temporary device of a sage, intended to arouse those of small faculties

by producing miracles through spiritual powers, to induce them to progress

further. Therefore they are not spontaneous powers. The Flower Ornament

Scripture says it is by the power of fundamental reality, because it is the

natural order, the way things are in truth, that it is possible to contain all

lands of Buddhas and sentient beings in one atom, without shrinking the worlds

or expanding the atom. Every atom in all worlds , like this, also contains all

worlds.

As The Flower Ornament Scripture says, enlightening beings attain

enlightenment in the body of a small sentient being and extensively liberate

beings, while the small sentient being does not know it, is not aware of it.

You should know that it is because Buddha draws in those of lesser faculties by

temporary teachings that they sec Buddha outside themselves manifesting

spiritual powers that come and go-in the true teaching, by means of inherent

fundamental awareness one becomes aware of the fundamental mind, and realizes

that one's body and mind, essence and form, are no different from Buddha, and

so one has no views of inside or outside, coming or going. Therefore Vairocana

Buddha's body sits at all sites of

enlightenment without moving from his original place; the congregations from

the ten directions go there following the teaching without moving from their

original places. There is no coming and

going at all, nothing produced by miraculous powers . This is why the scripture

says it is this way in principle, in accord with natural law. When the

scripture says time and again that is by the spiritual power of Buddha and also

thus in principle or by natural law, it says "by the spiritual power of

Buddha" to put forward Buddha as what is honorable, and says "it is

thus in principle" or "by natural law" to put forward the

fundamental qualities of reality. There is no change at all, because every

single land, body, mind, essence, and form remain as they originally arc and do

not follow delusion-all objects and realms, great and small, are like lights,

like images, mutually reflecting and interpen etrating, pervading the ten

directions, without any coming or going, without any bounds. Thus within the

pores of each being is all of space-it is not the same as the temporary

teaching of miraculous p owers with divisions, coming and going, which cause

illusory views differing from the fundamental body of reality, blocking the

knowledge of the essence of fundamental awareness of true enlightenment. This

is why the enlightening being Vimalakirti set forth the true teaching after

showing miracles. The Vimalakirti Scripture says, "Seeing the Buddha is

like seeing the true character of one's own body; I see the Buddha doesn't come

from the past, doesn't go to the future,

and doesn't remain in the present. "Because those of small views studying

the temporary teaching crave wonders , the enlightening being uses crude means

according to their faculties to induce them to learn, and only then gives them

the true teaching. One should not cling to phantoms as real and thus

perpetually delude the eye of knowledge. Recognizing the temporary and taking

to the true, one moves into the gate of the realm of reality. That which is

contrived can hardly accomplish adaptation to condi tions, whereas the

uncontrived has nothing to do. Those who

strive labor without accomplishment, while nonstriving, according with con

ditions, naturally succeeds . In effortless accomplish ment, effort is not wasted;

in accomplishment by effort, all effort is impermanent, and many eons of

accumulated cultivation eventually decays. It is better to instantly realize

the birthlessness of interdependent origination, tran scending the views of

the temporary studies of the three vehicles .

Fourth is the difference in the teachings set up in relation to

people of particular faculties . The Vimalakirti Scripture is directed toward

those of faculties corresponding to the two lesser vehicles, to induce them to

aim for enlightenment and enter the great vehicle. It is also directed at

enlightening beings who linger in purity, whose compassion and knowledge is not

yet fully developed, to cause them to progress further. Therefore, in the

scripture when a group of enlightening beings from a pure land who have come

here arc about to return to their own land and so ask Buddha for a little

teaching, the Buddha, seeing that those enlightening beings are lingering in a

pure land and their compassion and knowledge are not yet fully developed,

preaches to them to get them to study finite and infinite gates of liberation,

telling them not to abandon benevolence and compassion and to set the mind on

omnis cience without ever forgetting it, to teach sentient beings tirelessly,

to always remember and practice giving, kind speech, beneficial action, and

cooperation, to think of being in mediative concentration as like being in

hell, to think of being in birth and death as like being in a garden pavilion,

and to think ofseekers who come to them as like good teachers. This is

expounded at length in the Vimalakirti Scripture.

This Vimalakirti Scripture addresses those of the two and three

vehicles whose compassion and knowledge are not fully developed, to cause them

to gradually cultivate and increase compassion

and knowledge-it doesn't immediately point out the door of buddhahood,

and doesn't yet say that beginners in the ten abodes realize true

enlightenment, and doesn't show great wonders, because its wonders all have

bounds.

Fifth is the difference in the assemblies who gather to hear the

teaching. In the Vimalakirti Scripture, except for the great enlightening

beings such as Manjushri and Maitrcya and the representative disciples such as

Shariputra, all the rest of the audience are students of the temporary

teachings of the three vehicles . Even if there are enlightening beings therein

who are born in various states of existence and bring those of their kind

along, they all want to develop the temporary studies of the three vehicles, and

gradually foster progress; the scripture does not yet explain the complete

fundamental vehicle of the Buddhas. In the case of The Flower Ornament

Scripture, all those who come are riding the vehicle of the Buddhas-enlightcncd

knowledge, the virtues of realization, the inherent body of reality. They are

imbued with Universally Good practice, appear reflected in all scenes of

enlightenment in all oceans of lands, and attain the fundamental truth, which

conveys enlightenment. There is not a single one with the faculties and

temperament of the three vehicles ; even if there are any with the faculties

and potential of the three vehicles, they are as though blind and death,

unknowing, unaware, like blind people facing the sun, like death people

listening to celestial music.

Vessels of the three vehicles who have not yet consummated the p

ower of the Way and haven't turned their minds to the vehicle of complete

buddhahood are always in the sphere of Buddhas in the ocean of the realm of

reality, with the same qualities and same body as Buddha, but they never are

able to believe it, are unaware of it, do not know it, so they seck vision of

Buddha elsewhere. As The Flower Ornament Scripture says, "Even if there

arc enlightening beings who practice the six ways of transcendence and

cultivate the various elements of enlightenment for countless billions of eons,

if they have not heard this teaching of the inconceivable quality of Buddha, or

if they have heard it and don't believe or understand it, don't follow it or

penetrate it, they cannot be called real enlightening beings, because they

cannot be born in the house of the Buddhas ." You should know the

audiences are totally different-in the Vimalakirti Scripture the earthlings are

not yet rid of discrimination, while the group from a pure land retain a notion

of defilement and purity. Such people's views and understanding are not yet

true-sticking to a pure land in one realm, though they be called enlightening

beings, they are not well rounded in the path of truth and they don't

completely understand the Buddha's meaning. Though they aspire to enlighten

ment, they want to remain in a pure land, and because they set their minds on

that, they are alienated from the body of reality and the body of knowledge.

For this reason the Saddharmapundarika Scripture says, "Even countless

nonregressing enlightening beings cannot know. " As for the audience of

The Flower Ornament, their own bodies are the same as the Buddha's body, their

own knowledge is the same as the Buddha's knowledge; there is no difference.

Their essence and characteristics contain unity and multiplicity, and sameness and distinction. Dwelling in

the water ofknowledge of the realm of reality, they appear as dragons; living in

the mansion of nirvana, they manifest negativity and positivity, to develop

people. Principal and companions freely interreflect and integrate, teacher and

student merge with one another, cause and effect interpenetrate. All of The

Flower Ornament audience are such people.

Sixth, regarding the difference in doctrines set up, the

Vimalakirti Scripture uses the layman Vimalakirti manifesting a few

inconceivable occult displays to cause those of the two lesser vehicles to

change their minds. Also Vimalakirti, in the midst of birth and death, appears

to be physically ill to have people know defilement and purity are nondual.

Also the scripture represents the great compassion of the enlightening being,

the "enlightening being with sickness" accepting the pains of the

world, and extensively sets forth aspects of nonduality. It sets up concen

tration and wisdom, contemplation and knowledge, which it uses to illustrate

that the principle of nonseeking is most essential. Thus it says, "Those

who seek truth should not seek anything. " Nevertheless, it is not yet

comparable to The Flower Ornament's full exposition of the teachings of

sameness and distinction and cause and effect of the forms of practice of five

and six levels-ten abodes, ten practices, ten concentra tions, ten

dedications, ten stages, and equalling enlightenment.

Seventh, regarding the difference of the activity manifested by

the enlightening being Vimalakirti, in order to represent great compassion

Vimalakirti appears to enter birth and death and shows the actions of its

ailments. In The Flower Ornament Scripture Vairocana, by great compas sion,

appears to enter birth and death and accomplish the practice of true

enlightenment, illustrating great knowledge able to appear in the world.

Eighth, regarding the difference in the locations of the

teachings, the expounding of the Vimalakirti Scripture takes place in a garden

in the Indian city of Vaishali and in Vimalakirti's room; the expounding of The

Flower Ornament Scripture takes place at the site of enlightenment in the

Indian nation of Magadha, and in all worlds, and in all atoms.

Ninth, regarding the difference in the company of the Buddha, at

the time of the preaching of the Vimalakirti Scripture, the Buddha's constant

company consisted of only five hundred disciples; at the time of the preaching

of The Flower Ornament, all the Buddha's company were great enlightening beings

of the one vehicle, and there were as many of them as atoms in ten

buddha-fields, all imbued with the essence and action of Universally Good and

Manjushri.

Tenth, regarding the difference in the bequest of the teaching, in

the Vimalakirti Scripture's book on handing over the bequest it says that

Buddha said to the enlightenment being Maitreya, "Maitreya, I now entrust

to you this teaching of unexcelled complete perfect enlighten ment, which I

accumulated over countless billions of ages. " Thus the teaching of this

scripture is bequeathed to those who have already become enlightening beings

and have been born in the family of Bud dhas. In The Flower Ornament Scripture's

book on manifestation of Buddha, the bequest of the teaching of the scripture

is made to ordinary people who as beginners can see the Way and be born in the

family of Buddhas. Why? This scripture is difficult to penetrate-it can only be

explained to those who can realize it by their own experience. This represents

the three vehicles as temporary, because the sage exhorts cultivation and

realization in the three vehicles , and anything attained is not yet real, and

because the doctrines preached are not yet real either. Therefore The Flower

Ornament Scripture says, "The treasure of this scripture does not come

into the hands of anybody except true offspring of Buddha, who are born in the

family of Buddhas and plant the roots of goodness, which are seeds of

enlightenment. If there are no such true offspring of Buddha, this teaching will scatter and perish before

long." It may be asked, "True offspring of Buddha are numberless-why

worry that this scripture will perish in the absence of such people?" The

answer to this is that the intent of the scripture is to bequeath it to

ordinary people to awaken them and lead them into this avenue to truth, and

therefore cause them to be born in the family of Buddhas and have them prevent

the seed of buddhahood from dying out. Thus ordinary people are caused to gain

entry into reality. If it were bequeathed to great enlightening beings, the

ordinary people would have no part in it. The sages made it clear that if there

were no ordinary people who study and practice, the seed of buddhahood would

die out among ordinary people, and this scripture would scatter and perish.

This is why the scripture is bequeathed to ordinary people, to get them to

practice it; it is not bequeathed to already established great enlightening beings

who have long seen the Way.

As for the similarity of means of entering the Way, the

Vimalakirti Scripture says, "Those who seek the truth shouldn't seek

anything, " and "Seeing Buddha is like seeing the true character of

one's own body; I see the Buddha does not come from the past, go to the future, or remain in the present,

" and so on. These doors of knowledge of elementary contemplations are

about the same as The Flower Ornament Scrip ture, but the forms of practice,

means of access, order, and guidelines are different.

Next, to compare the Saddharmapundarika Scripture to The Flower

Ornament Scripture, the Saddharmapundarika is based on merging the temporary in

the true, because it leads people of lesser, middling, and greater faculties

into the true teaching of the one vehicle, draws myriad streams back into the

ocean, returns the ramifications of the three vehicles to the source. Scholars

of the past have called this the common teaching one vehicle, because those of

the three vehicles all hear it, whereas they called The Flower Ornament the

separate teaching one vehicle, because it is not also heard by those of the

three vehicles . The Saddharmap undarika induces vessels of the temporary

teaching to return to the real; The Flower Ornament teaches those of great

faculties all at once so they may directly receive it. Though the name

"one vehicle" is the same, and the task of the teaching is generally

the same, there are many differences in the patterns. It would be impractical

to try to deal with them exhaustively,

but in brief there are ten

points of difference: the

teachers; the emanation of lights; the lands; the interlocutors who request the

teaching; the arrays of the assemblies, reality, and emana tions; the

congregations in the introduction; the physical transformation and attainment

of buddhahood by a girl ; the land where the girl who attains buddhahood lives;

the inspirations of the audiences; and the predictions of enlightenment of the

hearers.

First, regarding the difference in the teachers, the exposition of

the Saddharmapundarika is done by an emanation or phantom-body Buddha; a Buddha

who passed away long ago comes to bear witness to the scripture, and the

Buddhas of past, present, and future alike expound it. The Flower Ornament is

otherwise; the main teacher is Vairocana, who is the real body of principle and

knowledge, truth and its reward, arrayed with embodiments of virtues of

infinite characteristics. The Buddhas of past, present, and future arc all in

one and the same time; the character istics realized in one time, one cosmos,

reflect each other ad infinitum without hindrance. Because past and present are

one time, not past, present, or future, therefore the Buddhas of old are not in

the past and the Buddhas of now have not newly emerged. This is because in

fundamental knowledge essence and characteristics are equal, noumenon and

phenomena are not different. Thus the fundamental Buddha ex pounds the

fundamental truth. Because it is given to those of great faculties all at once,

and because it is not an emanation body, it is not like the Saddharmapundarika,

in which there is an ancient Buddha who has passed away and a present Buddha

who comes into the world and expounds the Saddharmapundarika.

Second, regarding the difference in emanation of lights, when ex

pounding the Saddharmapundarika the Buddha emanates light of realiza tion from

between his eyebrows; the range of illumination is only said to be eighteen

thousand lands, which all turn golden-there is still limitation, and it doesn't

talk of boundless infinity. Therefore it only illustrates the state of result,

and not that of cause. The Flower Ornament has in all ten kinds of emanation of

light symbolizing the teaching, with doctrine and practice, cause and effect; this

is made clear in the scripture.

Third, regarding the difference in the lands, when he preached the

Saddharmapundarika, Buddha transformed the world three times, causing it to

become a pure land; he moved the gods and humans to other lands, and then placed

beings from other hands here, transforming this defiled realm into a pure

field. When The Flower Ornament was expounded, this world itself was the Flower

Treasury ocean of worlds, with each world containing one another. The scripture

says that each world fills the ten directions, and the ten directions enter

each world, while the worlds neither expand nor shrink. It also says the

Buddhas attain the Way in the body of one small sentient being and edify

countless beings, without this small sentient being knowing or being aware of it. This is just because the ordinary and the sage are

the same substance-there is no shift. Within a fine particle self and other are

the same substance. This is not the same as the Saddharmapundarika Scripture's

moving gods and humans before bringing the pure land to light, which is set up

for those of the faculties of the temporary teaching, who distinguish self and

other and linger in views.

Fourth, regarding the difference in the main interlocutors who

request the teaching, in the case of the Saddharmapundarika, the disciple

Sharipu tra is the main petitioner. In The Flower Ornament, the Buddha has

Manjushri , Universally Good, and enlightening beings of every rank each

expound the teachings of their own status-these are the speakers. The Buddha

represents the state of result: bringing up the result as the cause, initiating

compassionate action, consummating fundamental knowledge, the being of the

result forms naturally, so nothing is said, because the action of great compassion

arises from uncreated fundamental knowl edge. Manjushri and Universally Good

represent the causal state, which can be explained; Buddha is the state of

result, enlightening sentient beings. The vast numbers described in the book on

the incalculable can only be plumbed by a Buddha-they are not within the scope

of the causes and effects of the five ranks of stages; hence this is a teaching

within the Buddha's own state, and so Buddhist himself expounds it. The book on

the qualities of Buddha's embellishments and lights is Buddha's own explanation

of the principles of Buddhahood after having himself fulfilled cause and

effect. The teachings in this book of the perpetual power of natural suchness

and the lights of virtue and knowledge also do not fall within the causes and

effects of the forms of practice in the five ranks of ten stages, and so the

Buddha himself explains it, making it clear that buddhahood does not have

ignorance of the subtle and most extremely subtle knowledge. The rest of the

books besides these two are all teachings of the forms of practice of the five

sets or ranks of stages, so the Buddha does not explain them himself, but has

the enlightening beings in the ranks of the ten developments of faith, ten

abodes, ten practices, ten dedications, and ten stages explain them: the Buddha

just emanates lights to represent them. In the exposition of The Flower

Ornament Scripture there is not a single disciple or lesser enlight ening

being who acts as an interlocutor-all are great enlightening beings within the

ranks of fruition of buddhahood, carrying out dialogues with each other,

setting up the forms of practice of the teaching of the realization of

buddhahood to enlighten those of great faculties. Thus it takes the fruit of

buddhahood all at once, directly taking it as the causal basis; the cause has

the result as its cause, while the result has the cause as its result. It is

like planting seeds: the seeds produce fruit, the fruit produce seeds. If you

ponder this by means ofthe power of concentration and wisdom, you can sec it.

Fifth, regarding the differences in the arrays of the assemblies,

reality and emanations, in the assembly of the Saddharmapundarika Scripture,

the billion-world universe is purified and adorned, with emanation beings filling

it, and the Buddhas therein also are said to be emanations. In the assemblies

of The Flower Ornament Scripture, however, the congregations all fill the ten

directions without moving from their original location, filling the cosmos with

each physical characteristic and land reflecting each other. The enlightening

beings and Buddhas interpenetrate, and

also freely pervade the various kinds of sentient beings. The bodies and lands

interpenetrate like reflections containing each other. Those who come to the

assemblies accord with the body of embellishment without dissolving the body of

reality-the body of reality and the body of embellishment arc one, without distinction; thus the forms are

identical to reality, none are emanations or phantoms. This is not the same as

other doctrines which speak of emanations and reality and have them mix in

congregations.

Sixth, regarding the difference of the congregations in the

introductions, in the assembly of the Saddharmapundarika, first it mentions the

disciples of Buddha, who are twelve thousand in all , then the nun

Mahaprajapati and her company of six thousand-she was the aunt of Buddha; then

it mentions Yashodhara, who was one of the wives of Buddha, then eighty

thousand enlightening beings, and then the gods and spirits and so on. The Flower Ornament Scripture is not like

this: first it mentions the leaders of the enlightening beings, who are as

numerous as atoms in ten buddha-worlds, and doesn't talk about their followers;

then it mentions the thunderbolt-bearing spirits, and after that the various

spirits and gods, fifty-five groups in all . Each group is different, and each

has as many individuals as atoms in a buddha-world, or in some cases it simply

says they are innumerable. The overall meaning of this is the boundless cosmos

of the ocean of embodiments of Buddha each body includes all, ad infinitum,

without bounds. One body thus has the

cosmos for its measure; the borders of self and other are entirely gone. The

cosmos, which is one's own body, is all-pervasive; mental views of subject and

object are obliterated.

Seventh, regarding the difference of physical transformation and

at tainment of buddhahood by a girl, in the Saddharmapundarika Scriptu re a

girl instantly transforms her female body, fulfills the conduct of enlight

ening beings, and attains buddhahood in the South. The Flower Ornament Scrip

ture is not like this; it just causes one to have no emotional views, so great

knowledge is clarified and myriad things are in essence real, without any sign

of transformation. According to the Vimalakirti Scrip ture, Shariputra says to

a goddess, "Why don't you change your female body?" The goddess says

to Shariputra, "I have been looking for the specific marks of 'woman' for

twelve years but after all can't find any what should I change?" As

another woman said to Shariputra, " Your maleness makes my femaleness.

" You should know myriad things are fundamentally "thus"-what

can be changed? In The Flower Ornament Scripture's book on entry into the realm

of reality, the teachers of the youth Sudhana-Manjushri and Samantabhadra

(Universally Good), monks, nuns,

householders, boys, laywomen , girls, wizards, and Hin dus-fifty-three people,

each are imbued with the conduct of enlighten ing beings, each are replete

with the qualities ofbuddhahood; while they are seen to be physically

dissimilar according to the people who perceive them, it is not said that there

is transformation . If you see with the eye of truth, there is nothing mundane

that is not true; if you look with the mundane eye, there is no truth that is

not mundane. Because the Saddharmap undarika addresses those with lesser,

middling, and greater faculties for the temporary teaching, whose views are not

yet ended, to cause them to develop the seed of faith, it temporarily uses the

image of a girl swiftly being transformed and becoming a Buddha, to cause them

to conceive wonder, at which only will they be inspired to aim for true

knowledge and vision. They are not ready for the fundamental truth, yet they

develop roots of goodness. This illustrates inducing those in the three

temporary vehicles back to the one true vehicle. Also it cuts through the fixed

idea of time, the notion that enlightenment takes three eons, provoking

instantaneous realization that past, present, and future are in essence

fundamentally one time, without beginning or end, in accord with the equality

of things. It rends the net of views of the three vehicles, demolishes the

straw hut of the enlightening being, and causes them to wind up at the door of

the realm of reality and enter the true abode of Buddhas. This is why it has

that girl become Buddha, showing it is not a matter of long cultivation in the

past; the fact that she is only eight years old also illustrates the present is

not past study-the time of her transformation is no more than an instant, and

she fully carries out the fruition of buddhahood without the slightest lack.

Truth is funda mentally thus-there is no time in essence.

Those involved in temporary studies block themselves with views

and miss the truth by themselves-they call it a miracle that the girl attained

buddhahood, and do not know they themselves are originally thus; completely in

the world, how can they point to eons of practice outside? If they don't get

rid of this view, they will surely miss enlightenment forever; if they change

their minds and their views vanish, only then will they realize their original

abode. It would be best for them to stop the compulsion of views right now.

They uselessly suffer through eons of pain and fatigue before they return.

As for The Flower Ornament Scripture's doctrine of the

interdependent origination of the cosmos, it makes it clear that the ordinary

person and the sage arc one reality; if one still retains views, one is blocked

from this one reality. If one retains views one is an ordinary person; if one

forgets sentiments one is a Buddha. Looking downward and looking upward,

advancing and withdrawing, contracting and expanding, hu mility and respect,

are all naturally interdependent, and are all practices of enlightening

beings-there is nothing at all with transformable char acteristics having

birth, subsistence, and extinction. Therefore this Flower Ornament teaching is

not the same as the Saddharmapundarika's girl being physically transformed and

attaining buddhahood.

Eighth, regarding the difference of the land in which the girl who

becomes a Buddha dwells , in the Saddharmapundarika Scrip tu re it says this is

the world of nondefilement in the South, not this earth. This is interpreted to

mean that nondefilement refers to the mind attaining harmony with reality, and

"the South" is associated with clarity, emp tiness, and detachment.

However, if one abides in "the South" as a separate place, then self

and other, "here" and "there" are still separate this is

still following the three vehicles to induce those with facility for the

temporary teachings to develop resolution and finally come to the

Buddha-vehicle. This is because the residual force of attachment to the three

vehicles is hard to break. Yet there is some change of mind, and though the

sense of self and other is not yet obliterated, the mind is suddenly impressed

by the body of the cosmos. This is not the same as The Flower Ornament, in

which self and other interpenetrate in each atom, standing in a universal

relationship of mutual interdependence and interpenetration.

Ninth, regarding the difference in inspirations, the

Saddharmapundarika Scripture says that when the girl attained buddhahood, all the

enlightening beings and disciples on earth, seeing her from afar becoming a

Buddha and preaching to the congregation of the time, were delighted and paid

respects to her from afar. Subsequently it says three thousand people on earth

dwelt in the stage of nonregression, and three thousand people aroused the

determination for enlightenment and received predictions of their future

buddhahood. When these six thousand people paid honor to the girl from afar and

were inspired, their discrimination between "there" and

"here" was not gone-they just pursued the created enlightenment of

the temporary studies of the three vehicles,

and had not attained the enlightenment of fundamental awareness of the

cosmos in its universal aspect, in which

self and other are one being.

The Flower Ornament is not like this : in terms of the cosmos of

universality, the teaching of universal vision, the realm of absorption in the

body of the matrix of

enlightenment, and the teaching of the

array of the cosmic net of lndra, the subtle knowledge of the interpenetration

of the whirls of the oceans of worlds is all attained at once-because

realization of one is realization of all, detachment from one is detachment

from all. Therefore within one's own body are the arrays of oceans of lands of

the ten bodies of Buddha, and within the Buddha's bodies is the realm of one's

own body. They mutually conceal and reveal each other, back and forth, over and

over-all worlds everywhere are naturally this way . It is like myriad streams returning

to the ocean: even when they have yet entered the ocean, the nature of moisture

is no different; and once they enter the ocean, they all are of the same salty

flavor. The same is true of all sentient beings-though delusion and

enlightenment differ, the ocean of original buddhahood is basically not

different.

Tenth, regarding the difference of giving the prediction of

enlightenment to the hearers, in the Saddharmapundarika Scripture, though the

girl who becomes a Buddha reflects all at once the timelessness of the

cosmos, completely revealing buddhahood,

those in the temporary studies of the three vehicles , although they have

faith, have not yet gotten rid of their residual tendencies and are not yet

able to attain immediate realizations; because they can only ascend to

enlightenment over a long period of time, they are given prediction of

enlightenment in the distant future. This is not the same as The Flower

Ornament Scripture, which teaches that when one is deluded one is in the realm

of the ordinary, and when one is enlightened one is then a Buddha-even if there

are residual habits, one uses the knowledge and insight ofbuddhahood to cure

them. Without the knowledge and insight of buddhahood, one can only manage to

analyze and subdue habits and cannot enter the rapids of buddhahood, but can

only enter buddhahood after a long time.

Because the faculty of faith of beginners in the three vehicles is

inferior, they are not able to get rid of their bondage; they are fully wrapped

up in their many ties and arc obsessed with the vicissitudes of mundane life.

Though they seck to transcend the world, their capacities arc inferior and they

get stuck and regress. This is why the Buddha has them contemplate such points

as birth, aging, sickness, death, impermanence, impurity, instantaneous decay,

and continual instability to cause them to become disillusioned. When they

develop rejection of the world, their minds dwell on the distinction between

purity and defilement; for the benefit of this type of people, who, though they

cultivate compassion and knowledge in quest of buddhahood, still think of a

pure land as elsewhere, and because they have not obliterated their partial

views characteristic of the three vehicles and so always see this world as

impure, the Buddha explains cause and effect and settles their doubts, and

temporarily makes the world pure, and then withdraws his mystic p ower so they

will again see defilement.

Due to the habit of those in the three vehicles of viewing

everything in terms of impermanence, selflessness, and emptiness, their minds

are hard to change; though the girl in the Saddharmapundarika shows the Buddha

vehicle all at once, and though they believe in it, yet they cannot yet realize

it immediately themselves. For this reason the predictions of full

enlightenment in the Saddharmapundarika assembly all refer to long periods of

time. The Saddharmapundarika gradually leads to The Flower Ornament, whereupon

they are directly taught that the determination for enlightenment is itself buddhahood.

There are two aspects of similarity between the Saddharmapundarika

and The Flower Ornament Scriptures. One is that of riding the vehicle of

buddhahood directly to the site of enlightenment. The vehicle of bud dhahood

is the one vehicle. As The Flower Ornament Scrip ture says, among all people

there are few who seek the vehicle of hearers, Buddhism disciples, even fewer

who seek the vehicle of individual illumination, while those who seek the great

vehicle are very few; yet it is easy to seek the great vehicle compared to the

great difficulty of believing in The Flower Ornament teaching. The scripture

also says that if there are any people who are fed up and depressed or

obsessed, they are taught the path of disciples

to enable them to escape from suffering; to those who are somewhat clear and

sharp in mind the principle of conditioning is explained, to enable them to

attain individual illumination; to those who willingly practice benevolence and

compassion for the benefit of many, the path of enlightening beings is

explained; if there are any who are intent on the matter of greatest

importance, putting the teachings of infinite enlightenment into operation,

they are taught the path of the one vehicle. This is the distinction of four

vehicles in The Flower Ornament Scripture; as for the Saddharmapundarika, it

sets out three temporary vehicles and finally reveals the true teaching, which

is the Buddha vehicle-there is no real second or third vehicle. The four

vehicles of these two scriptures coincide in their definitions, but the manner

of teaching is different.

Then again in the Saddharmapundarika it says that "Only this

one thing is true-the other two are not real. " Going by this passage, it

seems to be setting up three vehicles , but actually it is four teachings: the

one thing which is true is the Buddha-vehicle, while the other two refers to

the great vehicle ofenlightening beings and the lesser vehicles of individ ual

illuminates and hearers, the latter being considered together because they are

alike in respect to their revulsion to suffering.

Also, the girl in the Saddharmapundarika reflecting the nature of

past, present, and future in one instant, and the statement that there is not

the slightest shift from ordinary person to sage, are about the same as the

teaching of the understanding and practice and entry into the Way by the youth

Sudhana in the last book of The Flower Ornament Scripture. As for Sudhana's

attainment of buddhahood in one life, within an instant he realized the nature

of past, present, and future is wholly equal. This and the girl's instant

transformation to buddhahood are both in accord with fundamental truth, because

this is the way things are.

As for the Nirvana Scripture, it is based on the buddha-nature. It

has ten points of difference with The Flower Ornament Scripture, and one

similarity. The differences are as follows : the location; the arrays of the

realms; the audiences; the interlocutors of the teachings; the audiences'

hearing of the teaching; the purity or defilement of the lands of reward; the

temporariness and reality of the Buddha-body; the patterns of birth and

extinction; the forms of practice of the teachings; and the models of

companionship. The one point of similarity is illustrated by the Nirvana Scripture's

image of an herb in the snowy mountains of such a nature that cows who eat it

produce pure ghee with no tinge of blue, yellow, red, white, or black.

Regarding the first difference, that of location, the Nirvana

Scripture is preached between the twin trees on the bank of the Hiranyavati

River in Kushinagara, whereas The Flower Ornament is preached under a jewel

enlightenment tree at the sight of enlightenment in Magadha.

Second, regarding the difference in array of the realm, when the Nirvana Scripture was

expounded, the hallowed ground between the trees was thirty-two leagues in

length and breadth, completely filled by a great congregation. At that time the

places where the boundless hosts of enlightening beings and their companies sat were infinitesimal, like

points: all the great enlightening beings from all buddha-lands came and

assembled. Also it says that at that time, by the Buddha's power, in all the

worlds in that billion-world universe the ground was soft, level, uncluttered,

free from brambles, and arrayed with myriad jewels like the western paradise of

the Buddha of Infinite Life. Everyone in this great assembly saw all the

buddha-lands, numerous as atoms, as clearly as seeing themselves in a mirror.

Also it says that the trees suddenly turned white. This is all extensively

described in the scripture.

Now when The Flower Ornament Scripture was expounded, there were

ten flower-treasury oceans of worlds, each with twenty layers above and below.

On the bottom layer there are as many vast lands as atoms in one buddha-field,

each with as many satellite lands as atoms in ten buddha fields; this

increases with each successive layer. All of the worlds in these oceans of

worlds have adamantine soil, with trees, pavilions, palaces, mansions, lakes, seas,

all adorned with precious substances. As the scripture says, "One time the

Buddha was in the land of Magadha, at the site of enlightenment in a forest,

having just realized true enlightenment: the ground was made of adamantine

diamond, adorned with discs of exquisite jewels, flowers of myriad jewels, and

clear crystals," and so on, going on to say how all the adornments of

inconceivable cons of all buddha-lands were included and revealed there. This

is eulogizing the adornments of the sphere of Buddha. This is also extensively

described in the book

on the Flower Treasury universe: these arc the adornments of the

Buddha's own body of true reward, not like in the Nirvana Scripture where

Buddha uses mystic power to temporarily

purify the world

for the assembly. The reason for this is that in the Nirvana Scrip ture

the audience is a mixture of those with the faculties of the three vehicles, so

there would be no way for them to see this purity by themselves without the

support of the Buddha's spiritual power. In the case of The Flower Ornament the

audience is pure and unmixed, being only those with the faculty for the one

vehicle; the disciples of the lesser vehicle who are in the crowd do not

perceive these adornments of Buddha's realm, because their faculties are

different. Although the scripture says "by the spiritual power of Buddha,

" afterwards it says, after all, that it is by the power of natural law

being so, or it is so in principle. Here, "spiritual" or

"mystic" means accord with reality; it doesn't mean that someone who

is actually an ordinary person is given a temporary vision. The Flower Ornament

basically shows the true reward, while the spiritual p ower of the Nirvana

Scrip ture is a temporary measure. Also, the Nirvana Scripture has Buddha's

pure land in the west, beyond as many buddha-lands as particles of sand in

thirty-two Ganges Rivers-it is not here.

This obviously is a projec tion, and not real.

Third, regarding the difference in the audiences, all in the

audience of the Nirvana Scripture are human or celestial in nature, with those

of the three vehicles coming together: except for the great enlightening

beings, when they remember the Buddha they weep; bringing fragrant firewood for

the cremation, they grieve and lament, missing the days when they attended the

Buddha. All such people arc suited to hearing

that the Buddha passes away;

except for the enlightening beings of the one vehicle who have penetrated

Buddha-knowledge, all the others are like this. The audience of The Flower Ornament

Scripture consists of enlightening beings in the ranks of fruition of

buddhahood, in the ocean of knowledge of essence, all of whom are on the one

vehicle. The humans, celestials,

spirits, etc. arc all of the same faculties and enter the stream of Buddha

knowledge. In the first assembly it says that the enlightening beings, as many

of them as atoms in ten buddha-worlds, are all born from the ocean of the roots

of goodness of Buddha. The ocean of roots of goodness is the ocean of knowledge

of the reality body of Buddha, born of great knowledge. All Buddhas have as

their basis the fundamental knowledge of the body of reality-if enlightening

beings were not born from this, all their practices would be fabricated.

This congregation, from the first

inspiration to the entry into the ocean of Buddha-knowl edge, go through six

levels, cultivating ten develop ments of faith, ten abodes, ten practices, ten

dedications, ten stages, and equaling enlightenment, from shallow to deep, the

forms of practice diverse. This is not like the Nirvana Scripture, in which the

three vehicles are alike included, and the good types of humans and celcstials

come to the same assembly; in The Flower Ornament Scripture, those of the three vehicles are not in the

congregation, or even if they are, they are as though deaf, not hearing. So you

should know the assembly of those of the three vehicles in the

Nirvana

Scripture-enlightening

beings, Buddha's disciples,

hu mans, celestials, etc. -- is

not the same

as that of

The Flower Ornament Scripture, which consists only of

enlightening beings in the one vehicle, whose rank when they first set their

minds on enlightenment is the same as the rank of Buddha, who enter the stream

of knowledge of Buddha, share the same insight and vision as Buddha, and are

true offspring of Buddha.

Fourth, regarding the difference in the interlocutors, in the

Nirvana Scripture the main petitioners for the teaching are the enlightening

being Kashyapa, the enlightening beings Manjushri and Sinhanada, and Shari

putra, and so on, who are models of the teachings. The Devil, who is also a

principal petitioner, urges the Buddha to pass away. As for The Flower Ornament

Scripture, the leaders who set up the teachings are Universally Good, Manjushri,